Detoxification of Ochratoxin A in Rice and Maize using ethanolic leaf extracts of Moringa oleifera and Vernonia amygdalina

Keywords:

Mycotoxins, Ochratoxin A, Detoxification, PhytochemicalsAbstract

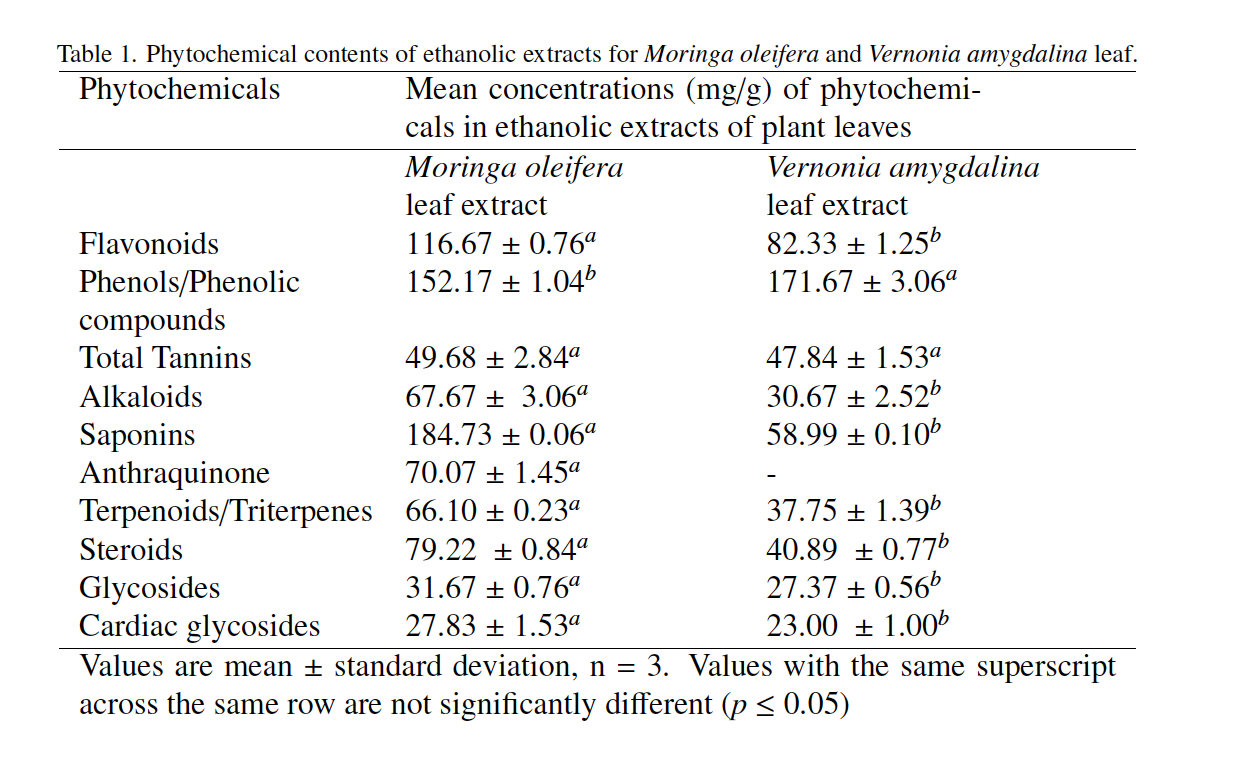

The non-availability of research data in North-central Nigeria coupled with the toxic and prevalent nature of ochratoxin A makes it necessary to quantity and identify possible remediative techniques that are effective, less toxic, locally available, cost friendly and easy to deploy. This research was aimed at evaluating the potency of phytochemical remediation on ochratoxin A (OTA) in stored rice and maize using ethanolic leaf extracts of Moringa oleifera and Vernonia amygdalina. High Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Ultraviolet/Visible detector (HPLC-UV/Vis spectroscopy) was employed in the determination of the detoxification levels of the OTA in the samples. Phytochemical constituents in the plant extracts were quantified using standard methods. Phytochemical concentrations ranged from 27.83 ± 1.53 – 184.73 ± 0.06 mg/g and 23.00 ± 1.00 – 171.67 ± 3.06 mg/g in the leaf extracts of Moringa oleifera and Vernonia amygdalina respectively. The levels of phytochemicals in Moringa oleifera extract were statistically (p ≤ 0.05) higher than in Vernonia amygdalina extract. OTA was present in all the samples with residual concentrations of 32.93 ± 2.02 and 39.23 ± 5.68 µg/kg in the stored rice and maize samples respectively. Detoxification using 1 – 5 mg/cm3 of Vernonia amygdalina leaf extract ranged from 34.80 (21.47 ± 1.76 µg/kg) to 56.67 % (14.27 ± 1.09 µg/kg) in rice and 38.87 (23.98 ± 0.95 µg/kg) to 58.45 % (16.30 ± 3.18 µg/kg) in maize while, detoxification using 1 – 5 mg/cm3 of Moringa oleifera leaf extract were ranged from 57.18 (14.10 ± 0.85 µg/kg) to 72.12 % (9.18 ± 0.30 µg/kg) in rice and 53.28 (18.33 ± 0.58 µg/kg) to 70.89 % (11.42 ± 1.52 µg/kg) in maize respectively. Detoxification efficiency of ethanolic leaf extracts of Vernonia amygdalina and Moringa oleifera on OTA increased with increasing concentrations of the extracts. Phytochemical detoxification of OTA in the stored rice and maize samples were observed to be efficient and promising with a detoxification order Moringa oleifera > Vernonia amygdalina.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Copyright (c) 2025 Oluwagbenga Anifowose, Bitrus W. Tukura, Obaje D. Opaluwa

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

How to Cite

Similar Articles

- Eno Chongs Mantu, Olukayode Olugbenga Orole, Aleruchi Chuku, Femi Gbadeyan, Tosin Okunade, Assessment of mycotoxin presence and distribution in maize grains across North central states of Nigeria , African Scientific Reports: Volume 4, Issue 3, December 2025

- O. U. Igwe, C. C. Oru, I. E. Otuokere, Chemical and bioprotective studies of Xylopia aethiopica seed extract and molecular docking of doconexent and cryptopinone as the prominent compounds , African Scientific Reports: Volume 3, Issue 2, August 2024

- Matthew Olaleke Aremu, Stephen Olaide Aremu, Ibrahim Aliyu, David Bala Passali, Munir Hussaini, Benjamin Zobada Musa, Rasaq Bolakale Salau, Amino acids profile and health attributes of Bambara groundnut (Vigna subteranea L.) and sesame (Sesamum indicum L.): a comparative study , African Scientific Reports: Volume 4, Issue 1, April 2025

You may also start an advanced similarity search for this article.