Assessment of mycotoxin presence and distribution in maize grains across North central states of Nigeria

Keywords:

Grains, Fungi, Mycotoxins, LC-MS, Hygiene, PrevalenceAbstract

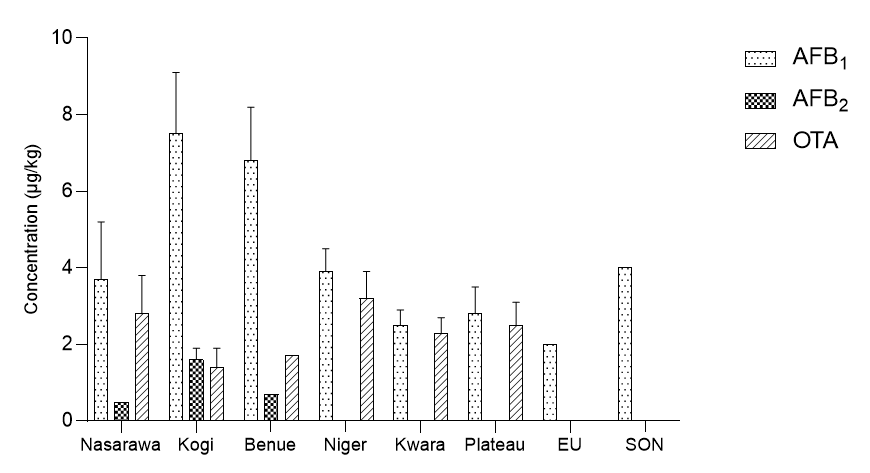

This research identified the prevalent fungal species and determined the concentration and distribution of mycotoxins in maize grains consumed in the North-central states of Nigeria. Six hundred composite samples were collected and screened for fungal contamination. The fumonisins, aflatoxins, ochratoxin, trichothecenes, and zearalenone concentrations were quantified in the samples using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Kogi State had the highest concentration of fumonisin B1 (FB1) (755.7±56.7 µg/kg), Deoxynivalenol (DON) (1211 µg/kg), zearalenone (ZEA) (313 µg/kg) and aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) (7.5±1.6 µg/kg) and B2 (1.6±0.3 µg/kg) respectively. Ochratoxin A (OTA) value in Benue State (3.2±0.7 µg/kg) exceeded the European Union (EU) recommended amount of 3 µg/kg, while AFB1 concentrations in Kogi State (7.5±1.6 µg/kg) and Benue State (6.8±1.4 µg/kg) exceeded the EU and Standard Organization of Nigeria (SON) recommended amount of 2 µg/kg and 4 µg/kg respectively. Trichothecenes concentrations were all low compared to the EU-recommended amount in maize grains meant for the table.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Copyright (c) 2025 Eno Chongs Mantu, Olukayode Olugbenga Orole, Aleruchi Chuku, Femi Gbadeyan, Tosin Okunade

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.