A mathematical framework for assessing food fraud intentions

Keywords:

Food fraud, Ethical fading, Unethicality, Bounded ethicality, Malicious intent, Similarity distanceAbstract

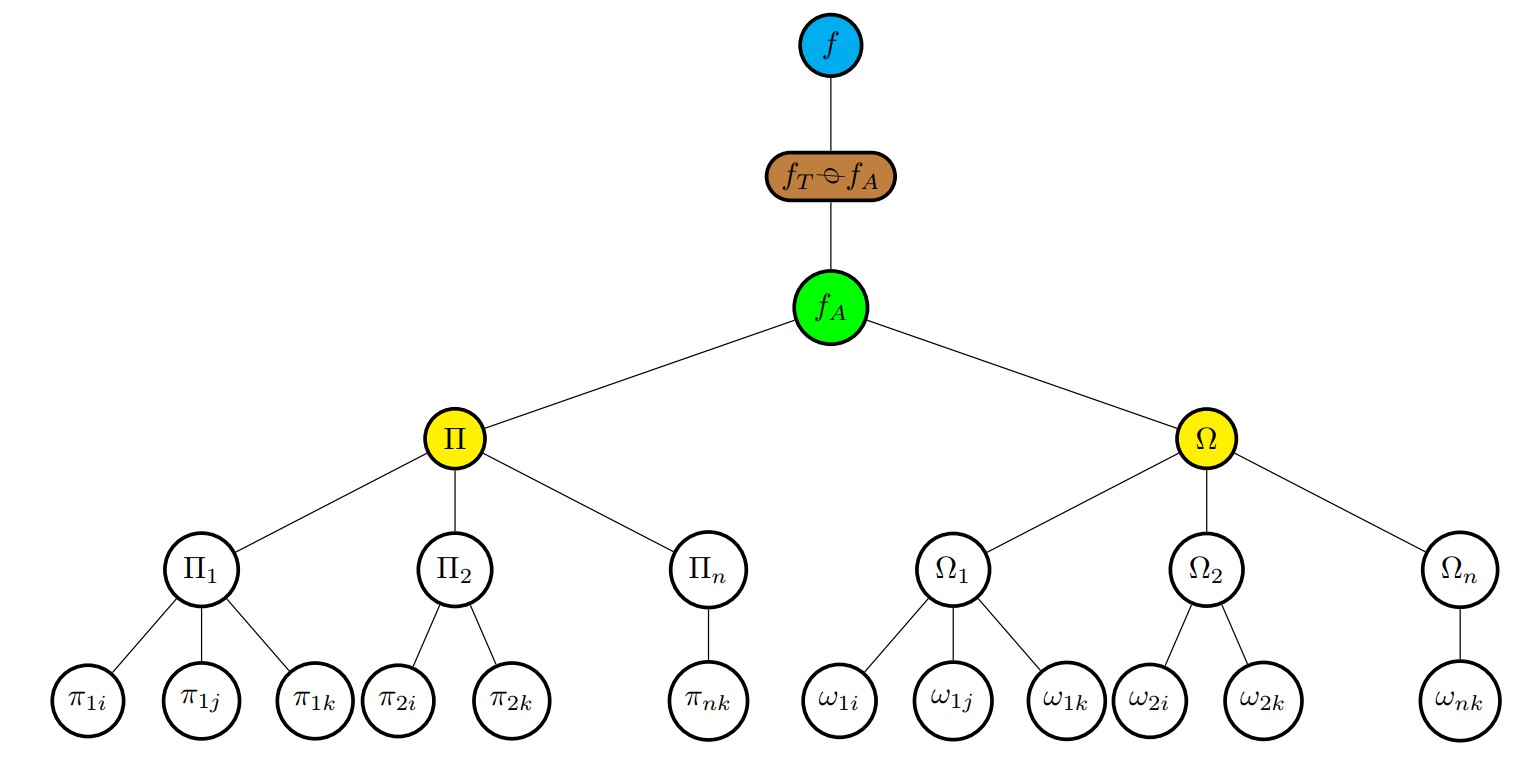

This work presents a framework for assessing subjects’ intentions to engage in food fraud. The model demonstrated that the decision to commit fraud arises from psychological mechanisms of malicious intent (Π) and ethical fading-bounded ethicality (Ω). Based on these psychological processes, the framework utilises a survey tool to generate finite sets of binary responses, fT (theorised response set derived from governing moral notions) and fA (actual response set given by subjects). The similarity function, fT ϕ fA, maps a dichotomous variable, with arguments (p, q), to a continuous variable, f [(p, q) 7→ f ]. The model metrics have Jaccard index characteristics with a range of 0.0-1.0, where fraud intention is low when f → 0.0 and high when f → 1.0. The number of questions used in a survey indicates special characteristics of the model, for instance, its rate of change (Rf ) and the number of possible response patterns (Γ). Survey data (N=54) was used to validate the model. The results show that the f values for respondents range from 0.21-0.69 with a mean of 0.44. Indicating that the respondents have moderate to neutral inclinations towards fraud. The statistical difference between f -values obtained from Π and Ω data indicates that they have the same effect on food fraud intention (p > 0.05). The model is essential when assessing the fraud intention of an individual or population by examining and understanding factors contributing to fraud and their numerical impacts. This is a significant step towards developing a fraud prevention framework.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Copyright (c) 2025 Shadreck Muyambo, Jack A Urombo, Garry K. Masoha, Livingstone Jenya

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

How to Cite

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Shadreck Muyambo, Jack A. Urombo, Temperature-dependent viscometry of baobab pectin (Adansonia digitata L.) , African Scientific Reports: Volume 3, Issue 1, April 2024